Elements of horror are naturally central to all of the books within this tradition, from Fear Street to Point Horror and beyond. But when the ‘90s teen horror trend collides with Halloween, there’s a whole different level of scares to be had with Halloween tricks, the looming fun—and potential danger—of Halloween parties, and costume-fueled subterfuge, confusion, and terror.

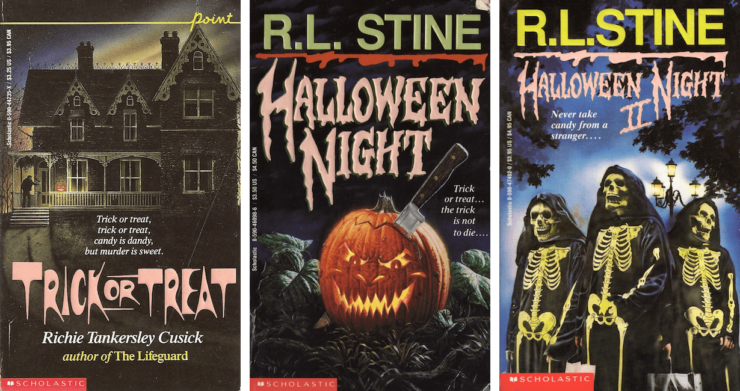

Richie Tanskersley Cusick’s Trick or Treat and R.L. Stine’s duo of Halloween Night and Halloween Night II are excellent examples of this ‘90s teen horror Halloween tradition. In each of these books, in addition to just trying to survive, the characters face the challenge of figuring out whether their lives are actually in danger or if the seeming threat is an ultimately harmless Halloween prank that just went a little too far, and just whose face resides behind those Halloween masks.

In both Cusick’s Trick or Treat and Stine’s Halloween Night, the respective heroines find one of the initial threats lurking just outside their bedroom windows, with Trick or Treat’s Martha looking out to find a dangling scarecrow banging against her window and Halloween Night’s Brenda pulling back her curtains to discover a Halloween mask staring back at her. Both of these instances are dismissed by their friends and family members as just a bit of Halloween fun, but these encounters also signal the ways in which for both Martha and Brenda, the horrors they are about to face will follow them home, as even their houses and their own bedrooms are not safe. In Trick or Treat, Martha soon discovers that a girl her age was violently murdered in her bedroom last Halloween. Between the house’s reputation among her peers, Martha’s suspicion of a ghostly presence, and passages hidden within the walls of the house, Martha is never really safe or at ease in her new home. In Stine’s Halloween Night books, Brenda’s stress at home comes from her cousin Halley, who has moved in with the family during her parents’ contentious divorce proceedings (and in Halloween Night II is adopted by Brenda’s parents and legally becomes her sister). Brenda is ousted from her bedroom so that Halley can move in there, the two girls are constantly fighting, and Halley is consistently Brenda’s first go-to suspect for the horrific happenings throughout both books.

While a scarecrow outside the window or a scary mask may be passed off as whimsical Halloween hijinks, some of the other pranks take a darker turn, including crank calls that quickly evolve into death threats (Trick or Treat), a decapitated bird in a jack o’ lantern (Halloween Night), a bed full of maggots (Halloween Night), and a moldy pumpkin in a locker (Halloween Night II), among others. The most extreme “is it a Halloween prank or a felony?” example, however, is cooked up by Brenda, the protagonist and purported “victim” of Halloween Night and Halloween Night II. While Brenda first proposes murdering her cousin Halley as a great plot for their Halloween story assignment for English class, this quickly evolves into a real life plan that Brenda describes as “fun” and “so easy,” which then morphs into a plan in which Brenda’s friend Dina decides to kill Brenda, stabbing the other girl in the chest at Brenda’s Halloween party. As with many other books in the ‘90s teen horror tradition, there’s a good deal of subterfuge and misunderstanding (Brenda was never really going to kill Halley, she just said she was going to in order to trick Dina into confessing, which doesn’t work and could actually hypothetically end up with Dina being just fine with Halley being murdered, as long as she herself also gets to murder Brenda, apparently). And no one actually dies. But when it comes to the question of intent, Dina is unrepentant, screaming at Brenda that “I still want to kill you!…I do! I really do!”

Buy the Book

Nothing But Blackened Teeth

The Halloween pranks in Trick or Treat are also potentially fatal. First, there’s the dark reminder of Elizabeth’s murder the previous Halloween and her missing/presumed dead suspected murderer ex-boyfriend, Dennis. The teens of Trick or Treat can’t fall back on the reassurance that no one will really get hurt when there’s at least one real, dead teenager to prove the legitimacy of the dangers they face. Martha is pursued through the darkened school hallways, falls down the stairs, and breaks her arm. Martha and her stepbrother Conor nearly die when their house is set on fire, Conor is stabbed a couple of times, and Martha is very nearly stabbed before a last-second rescue. Just like in Halloween Night, the villain is not some shadowy horror figure but another teenager and in this case, an actual murderer (rather than just being filled with rage and murderous intentions), having killed Elizabeth and Dennis the previous Halloween.

Trick or Treat, Halloween Night, and Halloween Night II are also really invested in the seemingly magical powers of disguise offered by Halloween costumes, which they use to conceal their identities, confuse others about who and/or where they are, and attempt to frame their peers in order to avoid detection. In Trick or Treat, Martha’s love interest Blake goes to the high school Halloween party dressed as Death. Despite several warning signs that Blake might not be a really good dude, Martha resists believing he might be the murderer, right up until she is attacked by someone wearing his Death mask (spoiler: it’s actually not Blake). Brenda’s wacky plan to murder Halley in Halloween Night relies on her and two of her friends switching costumes, with a confusion of clowns, peacocks, gorillas, and Frankenstein monsters leaving everyone not quite sure who is who. This plan is streamlined in Halloween Night II, when Brenda and her friends all wear the same costume, so no one will be able to tell them apart. In addition to confusing others, there’s also significant power in the costume for the wearer themselves: after donning the costume cloak or pulling on the mask, they engage in willful dissociation and are not quite themselves, capable of acts that they might not otherwise be able to commit (like murder).

Another interesting theme that connects these three books is the devastating effect of divorce on the characters themselves, reflecting a cultural preoccupation with rising divorce rates in the 1980s and ‘90s (though these rates actually held steady in the 1990s, rather than continuing to increase) and the dangers of “unconventional” families. In Halloween Night, Halley comes to live with Brenda’s family because her parents’ divorce has gotten ugly and Brenda’s home is supposed to offer Halley domestic refuge, though her dominant experience is more akin to sibling rivalry, with she and Brenda constantly at one another’s throats. Her parents’ divorce and the unsettled home life from which she has recently been transplanted are also blamed for some of Halley’s objectionable actions, such as making out with everyone else’s boyfriends. When Dina reveals herself as the attempted murderer, she tells Brenda that she was driven to kill her because Brenda wasn’t there for her when Dina’s parents got divorced and seeing Brenda shutting Halley out in the same way has triggered Dina’s rage and violence. In Halloween Night II, it isn’t the recently returned Dina but instead Brenda’s new friend Angela who ends up being the real danger, talking about how much her parents love Halloween, when it turns out that her parents are dead and Angela’s going home to two skeletons, as she launches her own murderous rampage.

In Trick or Treat, Martha comes to live in her creepy new house with her new family because her father has recently remarried, and he and his new wife have moved their blended family to this strange new town. Martha’s mother died a few years earlier and Conor’s parents divorced. Throughout the novel, Martha’s fear, anxiety, and difficulty finding her niche and academic balance at her new school are all chalked up to her need to adjust to this “rough” new reality, and she repeatedly reminds people that Conor is her stepbrother when they mistakenly refer to him as her brother. This unease echoes Martha’s emotional discomfort as well, as she works to figure out how and where she fits in this new family structure, as well as in her new home. Connor apparently earns the right to be called her brother by the end of the novel, after he has saved her life half a dozen times or so. Martha makes friends with three cousins—Blake, Wynn, and Greg—in her new town. Greg is an oddly balanced combination of peer and school guidance counselor and tells Martha that he understands what she’s going through, since he too comes from “a broken home.” Despite this self-identification, Blake, Wynn, and Greg are close and supportive of one another, always there when one of the others needs them. While divorce and non-traditional family structures serve as a kind of societal boogeyman in these novels, the relationships explored and developed in Trick or Treat instead reinforce the positive and affirming nature of these connections, both between the cousins and in the developing relationship between Martha and Conor.

Finally, the representations of mental illness in these novels is problematic and intimately connected with the Halloween theme, building on the challenge of distinguishing fiction and reality. After the conclusion of Halloween Night, Dina is hospitalized for residential psychiatric treatment, with her release and return a source of terror in Halloween Night II, as Brenda treats her coldly and regards her with suspicion as Dina tries to resume her former life and friendships. In Halloween Night II, Angela also has a compromised understanding of reality in her interactions with her skeleton parents and the way she manipulates and terrorizes her new friends. In Trick or Treat, characters spend the entirety of the novel trying to figure out who killed Elizabeth and tiptoeing around Wynn, who found Elizabeth’s body, in order to avoid further traumatizing the girl, as they maintain their silence about the murder around Wynn and avoid probing her repressed memories. However, they discover almost too late that Wynn herself is the murderer and has blocked the events from her mind, literally unable to remember what she has done and recalling only “the long dark” of the crawlspace that runs from the house to the cemetery in the woods. While there has been a great deal of speculation over Elizabeth’s love life, in the established tradition of policing girls’ and young women’s sexuality—she broke up with Dennis, got together with Blake, but was potentially on the verge of reuniting with Dennis last Halloween—it is actually Dennis’s love life that warranted further consideration by his peers, with his new girlfriend Wynn consumed by jealousy and rage. This schism is further exacerbated with Martha’s arrival, who bears a resemblance to Elizabeth and is now living in Elizabeth’s room, prompting Wynn to attack Martha and Conor, believing them to be Elizabeth and Dennis, as Wynn relives the horrors of last Halloween night.

This is a sensationalized and negative representation of mental illness that leaves little room for understanding, empathy, treatment, or healing for those characters who struggle with psychiatric issues. Mental health considerations are silenced here, actively ignored by the other characters, who argue that the best way to help Wynn is by not asking her any questions and allowing her to repress what happened last Halloween: if she remembers, then they’ll all have to deal with and respond to it, and it’s a lot easier to just not. Wynn’s attack on Martha and Conor actually upends and challenges the gendered treatment of mental illness throughout the rest of the novel: while young women shouldn’t be pushed to address these issues because they’re too frail to handle it and the truth might be dangerous to them, for the young men who might struggle with mental health issues, like Blake and Dennis, they themselves are seen as potentially dangerous, capable of outbursts of rage or violence. There’s no real sense of a growing awareness or that Wynn’s violence could have been prevented (at least in the second instance, in her attack on Martha and Conor—it’s already too late for Elizabeth and Dennis), or that she could have been productively helped through mental health treatment or a more proactive approach to working through her trauma.

While every day has its own potential for terror in ‘90s teen horror, Halloween is particularly significant. Costume parties are fun, but there’s a whole lot of boyfriend stealing and you’re likely to trip and fall at a party where the only source of light is the flickering candles of jack o’ lanterns (the impractical party lighting of choice in both Halloween Night and Trick or Treat). The nightmares of last Halloween can never really be laid to rest. Sometimes a prank is just harmless fun and sometimes it’s attempted murder, but it might be impossible to tell until it’s too late. And behind those masks, you never really know who’s who and who might be out to kill you.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.